I scrape my high-top chair closer towards the table, the thin metal legs screeching against the cement floor, the sound echoing unpleasantly across the near-empty restaurant. Everything about this dining experience is barren. The dining room is cold, the dishes lack garnish, plastic silverware comes wrapped in crinkly cellophane, and the menu is a QR code. Finally, I’m stuck by the lack of a saucer under my coffee cup.

Desaucerfication. The idea has been forming in my head slowly over the past decade, fueled by a bad experience here and an article there. Every time I noticed a missing tablecloth or had to pay $35 for seat selection on an airplane, the feeling intensified. The notion of desaucerfication is not merely a longing for the superior past, but a broader cultural shift that you can identify across a multitude of disciplines.

Let’s begin with cinema.

Crispy Movies

Though I didn’t know it, the first wisps of desaucerfication originally came to me in 2011, standing in the Walmart electronics section. One of the first episodes of Game of Thrones was playing on a large television, and I said to myself, “This looks terrible.” My skin crawled at the sharp outlines of characters, the speed at which everything moved, and every laid-bare detail. I was, in fact, looking at my first high-definition flatscreen television whose boasted “motion smoothing” feature resulted in the soap opera effect. I was also for the first time noticing the sad, industrial vibe of digital moviemaking, which contrasted sharply with the 35mm film we were used to.

There’s a reason 90’s romcoms are best enjoyed in the fall while wearing a sweater, or during a snowed-in Christmas afternoon. Movies produced in the late 20th century and early 21st exude a warm softness, almost like if you stroked the images they would have a velvety texture. It seems that just by putting them on, the temperature in the room increases by a few degrees. Blurred backgrounds, gentle lighting, and an ambient graininess work together to create a comforting illusion; a movie is a fantasy, and 35mm film makes it feel like exactly that. However, digital cinema started taking off in the mid-2000’s, and since 2016, over 90% of movies have been made digitally rather than on film, while 35mm has been relegated to a romantic, expensive niche medium.

35mm is the same resolution, by the way, as the disposable cameras that documented many of our childhoods, but that changed in the 2000’s. Who’d want to wait around for film to develop when you could see right away how that shot came out? With the advent of the iPhone’s pocket-sized digital camera ready at all times, consumers stampeded away from disposable film cameras in favor of ready-to-go digital photography. Little did we know, in exchange for efficiency, our memories, photos, and films were about to be desaucerfied.

Zombie Lights

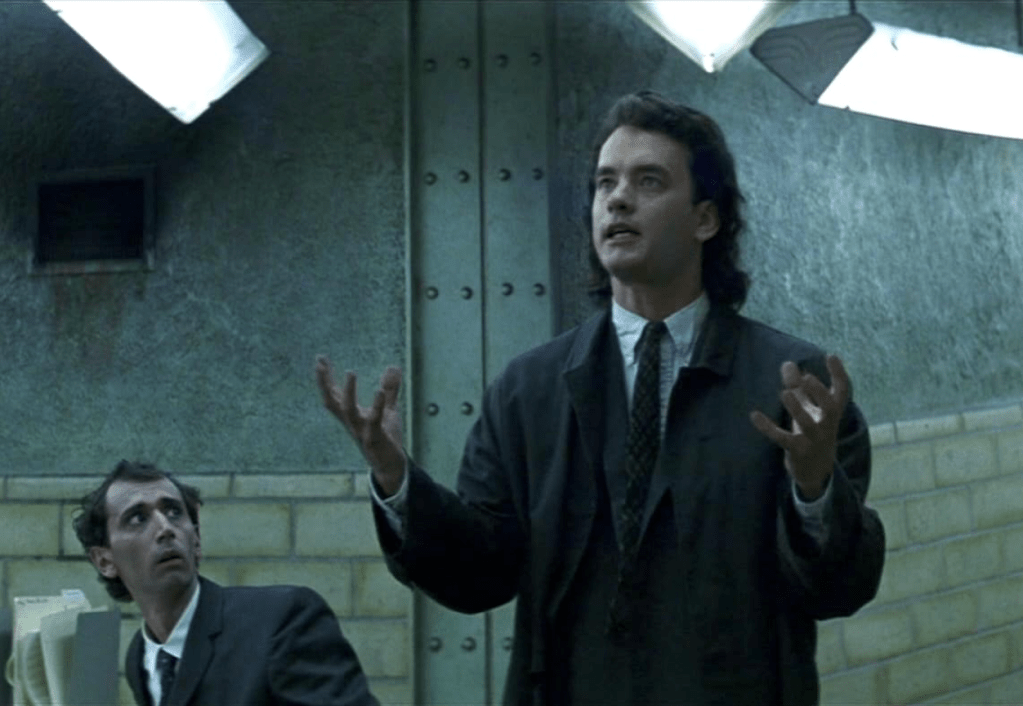

In 2007, the Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA) raised the national standard for lightbulb efficiency by 30%. Thanks to this act, home and municipal lighting became much more energy efficient. Since then, interior lighting has become harsher, whiter, and more exacting. Tom Hanks’ character in Joe vs. the Volcano recognized the emotional effects of harsh white lights iconically: “Not that anyone could look good under these zombie lights…I can feel them sucking the juice out of my eyeball. Suck, suck, suck, SUCK.”

Yellow light, on the other hand, has proven to be more relaxing than white light. Add a dash of blue into your white light, and your melatonin production drops by a quarter. This explains why reading before bed in the golden glow of a side table lamp results in much better sleep than viewing The Horrors on your phone for two hours. (Our parents were right—it was the damn phones this whole time.)

The EISA’s major concern with the old-style yellowish lightbulbs is that they lose a lot of energy through warmth. With the new, more cost-saving lighting, our lives became not only emotionally, but physically colder. And not coincidentally, more efficient.

Is there a connection between lost warmth and increased efficiency?

Loss of Saucers: Big Deal or Just Whining?

So is desaucerfication just an oddly specific gripe about how back in my day we had saucers under our cups? Or does it merely signify the direction of social and cultural change?

The saucer is not necessary to the caffeinating experience. You can get just as much coffee out of a styrofoam cup the same size, and you can save money on dishes. But when you’re presented with a teacup on a saucer, that little excess sends a message to your nervous system: You’re cared about. After analyzing how cinematographers exchanged their film cameras for digital, and how home and street lights went from a comforting yellow to a harsh, judgmental white, we can see what desaucerfication boils down to: increased efficiency often results in a loss of human warmth.

Industry

Filming digitally and using CGI effects and blue-screens all save time and money, as does using blue-white LED lighting instead of the old-style yellow bulbs. You can also save time and money by using less dishes, using online menus instead of printed cards, and serving terrible food on planes. But in the end, our stories, homes, and lives get a little colder.

The home appliance advertisements of the 50’s lied to us. Dishwashers don’t save you time so you can watch more TV, they save you time so you can get a second job to pay for the dishwasher. It’s becoming evident that in a consumer capitalist society, the goal of efficiency is not to have more time to yourself, but to do more work in less time, so you can have more time to do more work. Many people these days work two or three different jobs just to break even. We work so much to have so little.

The other day at the gym I saw an advertisement for a fold-up synthetic Christmas tree. It came pre-decorated, pre-strung with lights, and after Christmas you could telescope it down into a disc that stored easily. The whole selling point, it seemed, was that the ritual of putting up a tree and decorating it was a hassle. This fancy product allowed you to cut that down to a matter of minutes! The overlooked detail was that little rituals and personal touches make life worth living.

Claiming teleology here would be a mistake—I don’t believe that everyone in charge got together at a long table in an evil cave and decided that everything was going to be terrible forever. But our lives have become more industrial. There’s a subtle stress about picking hobbies that will benefit you in some monetary way. “You should learn this language because you’ll have more job opportunities. You should get good at art so you can sell it. You should start a travel vlog so you can become an influencer and sell ad spots.”

But I’m trying to shift my focus. Maybe the point of life isn’t to make as much money as possible, but to slow down and connect with others.

Leave a reply to zudlow Cancel reply