A safe, stationary space

I’ve always said that creation happens alone and in the dark. Whether it’s waking up hours before sunrise, or staying up long after everyone else has gone to bed, there’s something about the dark solitude that’s sacred and inspiring. And equally importantly, messy.

Creation, for me, happens in a stationary place. After ten years of travel, I can say with certainty that when I’m sitting on a bunkbed in a hostel, covered in sweat, waking up early the next morning to catch a train, I don’t exactly feel inspired to sketch or work on a novel. There have existed artists and authors more courageous and hardworking than me, like Georgia O’Keefe and Basquiat, who can build a body of work while traveling. I’ve just never had what they do. Years of my own long-form travel crystalized my personal creative philosophy: My creativity needs a space, and it needs to feel safe.

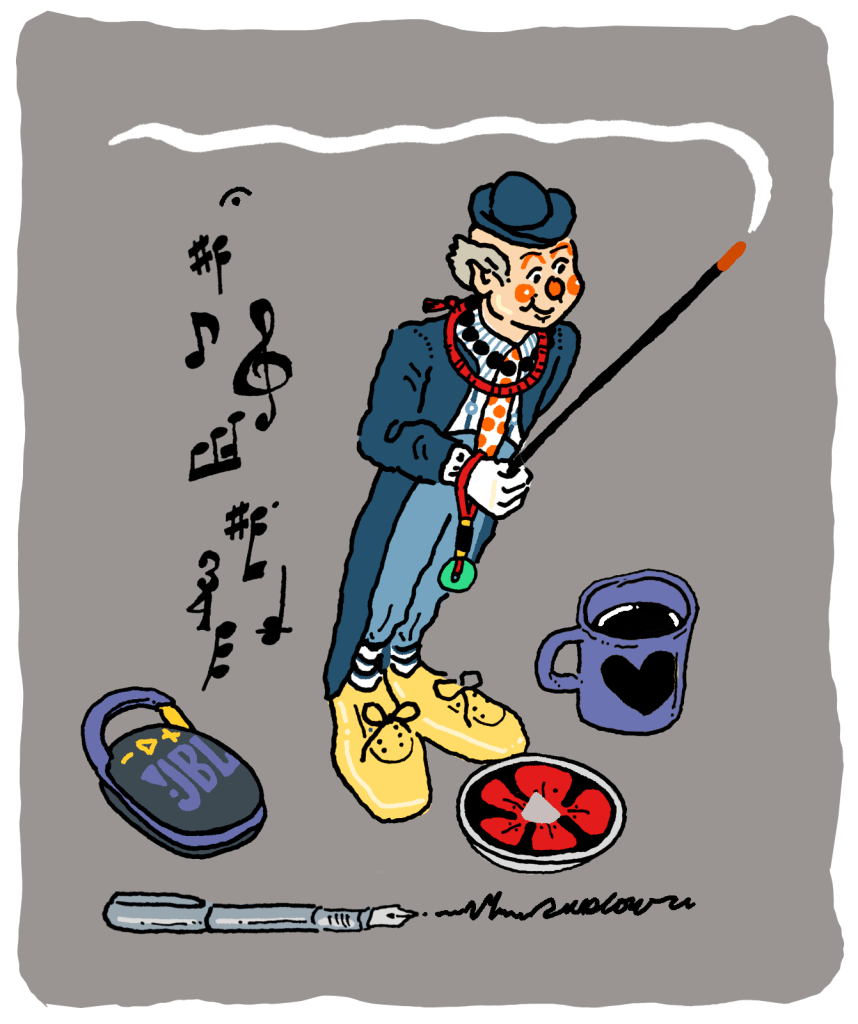

While I don’t have Umberto Eco’s library or Henri Mattise’s studio, I do have a desk, a lamp, and a incense holder in the shape of a clown. (His name is Gilchrist.) My ritual for carving out a safe creative space is simple: I pour myself a cold mug of yesterday’s coffee, do a quick tidy-up of my creative space, put on some lyric-free music, and light incense or a candle to finally set the stage. The ritual tells my body that I’m in a safe place where nothing can bother me. And with that, I’m free to create.

This isolation ritual is important because my muse has to know that nobody’s watching. I repeat a little verse while I work—this is just for me. Whether I’m typing dialogue, scribbling a rough draft of an illustration, or adding color to lines, stating that what I’m doing is “just for me” relaxes me into flow. I have nobody else’s expectations to live up to, and nobody is watching over my shoulder. “What if time ran backwards?” I ask myself in this judgment-free state, and my words fall on nobody’s ears, because it’s just me. “How would society change if people lived forever? What would instruments look like if we had twenty fingers instead of ten? What’s the color of hate? What number loses their car keys more often: 43 or 98?” Playful thought-springboards like this open up worlds of imagination. As soon as you induce judgment, you start second-guessing your attempts, stifling your experiments, and reining in your explorations. Judgment blocks the most fluid state of creativity, a dimension I’m trying to get to with the music and the incense and yesterday’s cold coffee. There’s a reason many religions have creation and judgment on opposite ends of the story: these two things don’t like to happen at the same time.

In The Beginning(?)

Religion influences the journeys of many American artists, and many grew up reading the Genesis creation story and inferring that the whole universe was made in a perfect state, from nothing, in an effortless week. Anything that happens after that is a fall from grace, a dip down to a lesser state that’s not only slightly, but hugely worse than what came before. While Genesis is not a peer-reviewed scientific paper with citations, we can read it as the literary beginning of many creative lives. I think we owe it to ourselves to consider how this definition of “creation/creativity” influenced how we went on to create in the decades that followed.

Creation, in fact, may be less like picking up a perfectly-formed gem off the forest floor, and more like sorting through rocks in a riverbed. This idea of refining and forming, rather than instantaneous perfection, lines up with creation stories from other religions, where drawn-out battles between clashing elements of order and chaos giving birth to the world we now live in. In Greek mythology, the universe comes from an entity called chaos (χάος), which is where we get our word. According to Alaskan Native cosmology, Raven orders the chaotic world into what we see today. Japanese folklore paints the beginning of the universe as an egg-shaped sea of disorganized matter. Unfortunately, none of us were there for it, and we can only ask questions that point us inward—is creation a single event of perfection, or is it a long-term refining of chaos that eventually leads to something “good enough?”

If it’s the latter, then why should we, as artists, be afraid of chaos and disorder?

The ex-nihilo idea of “from nothing, perfection” affects how we do creativity. We perfectionists tend to expect polished diamonds right off the bat, and anything short of that is deemed a “fall from grace.” I know there have been many times I gave up on a piece immediately because there was “something wrong with it,” or I just didn’t “feel inspired” anymore. Now I push myself to get messier. If I hate the first half of what I’ve drawn, I push myself through till the end. Because those chaotic, messy spaces are where I find new inspiration, startling ideas, and a sustainable excitement that goes beyond feeling inspired.

Not enemies, but cooperating concepts.

Creation and chaos, order and judgment. Though they seem like mutually-exclusive opposites, these pairs are really siblings. I know that because we can see this polarity operating in our own brains—two equal but opposite hemispheres living inside our skulls. Dr. Gabriele Rico addresses this tension in her book, Writing the Natural Way, in which she beautifully outlines the functions of the right and left brain.

The left brain, which controls the right side of the body, excels at making judgments, labeling experiences, and sorting things into categories. The left side of our brain is a mathematician, a logician, and an excellent sorter, making sense out of the universe for us. If the left side of your brain is a bow-tie-wearing librarian sorting books onto shelves by author and subject, the right brain is the artist living in the attic throwing paint onto canvases. It thrives on chaos, makes connections, draws parallels, and generally just catches vibes. While the left brain tells you the difference between day and night, the right brain tells you that what we call day and night are just two sides of the same rotating planet, and they’re not so different after all. It’s a lot more comfortable with contradictions, paradoxes, and messiness. And that kind of safe, judgment-free environment is the perfect nebula where new and disorganized ideas can be born.

On the other hand, the logical left side of the brain isn’t very good at creativity. That’s not to say it isn’t equally important; without the left brain, we’d lack the language and fine motor skills required for writing and drawing. If we were operating on the right side alone, thoughts and feelings would just sit in our heads rather than get out into the world in the form of words and images. So while credit goes where it’s due, if the organizational left brain butts in on the imaginative process, deeming ideas good and bad the second they’re conceived, creativity won’t just suffer. It’ll sputter out and vanish. I think the reason we started visualizing creativity as a muse that must be pampered is because it knows where it’s not welcome, and will slam the door on its way out.

Creativity is messy, sloppy, and many times, embarrassing. We have to let the process do its thing without controlling every movement from the beginning. We have to come up with stupid ideas and draw bad sketches and write unrealistic characters and try out questionable color schemes. We need to create boldly. We need to go with a feeling without knowing what’s going to happen. We need to create without a finished product in mind—no agenda, no destination, just a direction and a vibe and a safe space where it can happen. The sorting and polishing can happen much later.

We have no way of knowing how all of this started. But in our desktop microcosms, between glowing incense stick and day-old coffee, creation happens right in front of us. It’s not clean-cut or beautiful. There are no cherubs with trumpets announcing the sixth day of creation. Instead, we have half-formed characters spouting unnatural dialogue. We have pencil sketches of lopsided cars. In the dark, while the rest of the house is asleep, we have a blinking cursor on a blank page and the most half-assed idea of the next chapter of our novel. And while nobody’s watching, with no fear of making mistakes or getting laughed at, we create.

Leave a comment