A rising tension above my stomach, a shortness of phrase, a tightness of lips, babbling without quite knowing the direction the rant is taking me, and a vague sense of embarrassment. These are all the things I experienced recently when confronted with a simple line.

“Words can only hurt you if you give them the power to.”

The phrase was said confidently by an older man as we were driving in Southcentral Alaska’s Chugach and Talkeetna ranges, the sun in our faces for the first time in months. At the end of Alaskan winter, when the sun starts to reclaim its angles in the sky, psychological problems usually melt away mysteriously, but today my unconscious took me in the opposite direction. Printed on paper, the concept of giving words power to hurt seemed like sage advice for a stable life. But hearing it spoken out loud sparked something inside me. Like lighting a stick of incense, watching it burn slowly, redly, infusing the whole room with an unplaceable essence.

“Have you noticed,” he continued, “That we stopped saying ‘sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me?’ Now everyone’s all about safe spaces.”

I took a shallow, quick breath and responded on impulse. “It’s because we figured out that words do hurt,” I suggested, noting the shortness of my breaths and the tightness of my speech. “They hurt us deeply. And the hurt lasts a long time.” I was mad, and I didn’t want to be. Soon I was less focused on the conversation and more focused on what I was feeling: pissed off.

My pulse quickened just a little bit as slurs ran through my head. Neurons reached out and touched one another, flashing unprintable curses across my cerebellum. One in particular stood out: faggot. The word unleashed a memory of someone I talked to, years ago, so deeply wracked in self-hate towards being gay that he used the slur to slash himself. Hearing him talk about himself with such disgust, I can hardly bring myself to reclaim the word like so many others do. The F-slur triggered memories from the 2000’s of all the words that had volleyed back and forth over my head, shot by people who didn’t know they were talking about me. Limp-wrist. Sissy. Pervert.

Shapeless emotions are complex thoughts in masquerade. Here in the comfortable passenger seat of a warm van, surrounded by shining, shadowy mountains, I knew that this rage ignited by a simple motto was important, and if I shoved it down it would balloon up somewhere else, somewhere it was even less welcome. Now there were three of us in the car: Me, him, and the rage. As we drove between the stoic white-capped mountains, with the careless blue sky hanging overhead, I felt like I was the only thing in miles that cared deeply about anything, and that’s when I realized why I was so upset.

We don’t give words the power to hurt us, because that’s not a choice we can make.

As someone’s vitriol connects with your ears, it sends a signal to your brain and forms a picture—seen, felt. There are some incredibly brave people in the world who have steeled themselves against these words, who have chosen to reclaim the language and the curses and the slurs, and I admire those people. But actively perfecting that skill is the choice in question. Lacking the skill is just the natural state. You can choose to rise above, but you do not choose to be hurt.

A ski crash left a scar on my wrist, but that hasn’t affected how I eat or who I open up to or how I treat strangers. But words—a misplaced comment when I was five, a mean jab at the playground when I was ten, a cruel joke overheard in high school—created foundational scars that have shaped how I grew and changed and interacted with life. And in that way, words hurt us much more deeply than sticks and stones ever can.

Feelings remain a primal directive rather than a choice. A feeling is involuntary, uncontrollable, ancient, something that sparks in your spiritual internal combustion engine, and that information is relayed up to your conscious mind. From there, your material response is the only choice you can make.

One day, several Aprils ago, I finally accepted that I had no real choice in who I felt attraction towards (men, if you haven’t figured that out by now); that trait was something that resonated from deep in the back of my brain, deep in my body, and no amount of self-shame or repentance or discipline would (or could) rewire that aspect of me. And that’s the incense stick that was lit by the old man’s well-meaning advice: I didn’t choose to be affected by words any more than I choose to be gay. And I’m done feeling ashamed of either phenomenon.

There’s a lot of language right now, specifically in political discourse, about the dangers of feelings. “Facts don’t care about your feelings,” self-important pundits preach from podiums at paid events. “Boo-hoo, snowflakes get triggered by words,” they jeer during their hate campaign on preferred pronouns. “Get over it, I’ve got freedom of speech,” they claim, while supporting a man who dictates which words the CDC can and can’t use in medical publications.

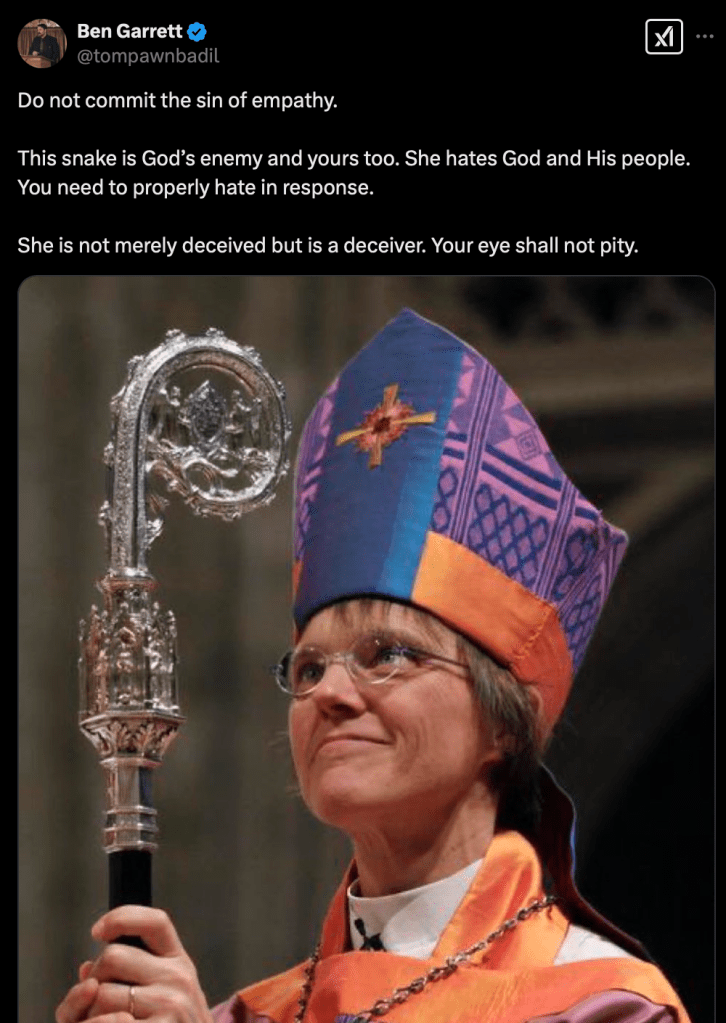

One of the most hilarious illustrations of this self-inflated, new-wave, grumpy hard-assery is Ben Garrett’s laughable tweet response to Bishop Mariann Budde’s beautiful words on kindness towards immigrants and queer people. “Do not commit the sin of empathy,” genuinely just makes me laugh, as does the footnote under the tweet: “Readers added context: Empathy is not a sin.”

The horrifying notion that feeling emotion is the dark path is extremely prevalent among contemporary religious Americans. And personally, I’m tired of listening to people explain not only how orphan-crushing machines are “actually really good for orphans,” but how funding orphan crushing machines is our religious prerogative.

The ability to feel strongly about people and issues is one of the most beautiful features of our species. Empathy should be cultivated, not scoffed at. We should shed tears over injustices that don’t have anything to do with us, rage against the erosion of the other gender’s rights, and fight passionately for people who we have nothing in common with. Passion and anger are as integral to our design as love and empathy. We should choose words that build up and heal people, not purposefully select the harshest words possible for the sake of “telling it like it is.” And if we get hurt along the way, let’s not blame ourselves for not being tough enough. Toughness is an attempt to make life easier on yourself, but the real work is in staying tender.

I won’t be curtailing my anger, and I won’t be apologizing for feeling things deeply.

Leave a reply to George Powell Cancel reply