No. It’s not.

When I tell people I can speak Mandarin, they’re usually surprised, and say, “Wow! That must have been a hard language to learn!”

I don’t know how to tell them that I finally settled on Mandarin because I’m lazy. I don’t know how to tell them that in all the languages I’ve tried to learn, Mandarin has been the easiest.

In this blog post you’re going to learn why Chinese is a LOT less scary than it looks, and by the end of the article I’m going to try to convince you to start learning today.

Also, before anyone corrects me, I use the words Chinese and Mandarin interchangeably. If you want to know what the difference is, you can watch my latest YouTube video on the different Chinese words for Chinese.

There will also be some great resources for learning at the end of this post, so if you want to cut right to the meat just scroll to the bottom of the page.

Why I Learned

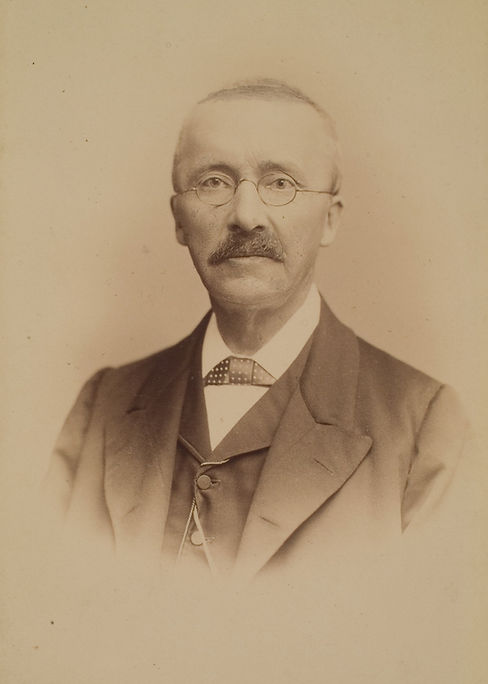

Since I was a teenager, my academic role model was archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann. He started learning Ancient Greek when he was a boy, and developed a system of language learning that let him learn any language in six weeks. Some reports said he knew as many as eight or nine languages in his lifetime.

That man was living the DREAM, in my opinion.

I started my language quest in high school, learning Italian with Rosetta Stone, and got pretty good at it. I went on to dabble in Spanish and Portuguese, finally settling on Russian as I was turning twenty. After that, I got into French.

But despite all my work, I would always hang just below conversational level.

Chinese didn’t even cross my mind until my second year in college, when I learned that I had one free elective that I could use however I wanted. Basically, I picked Chinese for the bragging rights.

But as the months went by, it was gelling like no other language had, and here’s why.

Grammar

Here’s the top point for me. I have ALWAYS. And I repeat, always hated verb conjugation. Mostly because of the inconsistency of it. It’s the wall I consistently ran into with Russian, French, and Italian.

But, guess what? Chinese doesn’t conjugate.

Chinese doesn’t give a dime about who the subject is and what the object is. Chinese doesn’t know what a noun case is, or what a verb tense is. The verb for drive is never drives or drove or driven or driving or driven’t.

With Mandarin, you just stick words together like lego blocks, adding this and that until you get sentences. I’d be lying to tell you there’s no grammar in Chinese, but what exists is intuitive and simple.

Tones

People have a number of pre-loaded excuses for why they don’t want to learn Mandarin. One of them is, “Chinese is hard to learn because it’s a tonal language.”

If you’re reading this blog post, it means you learned how to speak English at some point in your life. And if you learned how to speak English, you’ve also perhaps realized you can mean different things by saying a sentence two different ways.

“You’re the nicest person here,” is a compliment, but “You’re the nicest person here,” implies that there was a dog in the room that outpaced you in kindness.

Well, that’s tonality, and it’s something English speakers know intuitively. We learn it, there are rules for it, but we never talk about it.

Chinese uses tonal marks ( ā á ǎ à a ) to indicate flat, rising, dipping, or falling tones. English? You just have to hear it out loud. And while the tones in Chinese denote meaning (e.g., they don’t change from sentence to sentence), in English tones connote emotion.

Oh, I forgot, we also have meaning-bound tones in English, too. In fact, you can do a little experiment and see it for yourself.

How do you say record, as in “the black vinyl disc that plays music?” Now, how do you say record, as in “to use a microphone to save sound?”

Say the two words out loud. If we apply tonal marks to the two different words (record noun vs. record verb), you’ll find that the noun is rècǒrd, but the verb is rěcòrd.

What I’m saying is that you’ve already learned to master a tonal language. Once you embrace this fact, it makes it easier to wrap your head around tonality in a language. Bottom line: the only reason tonal languages are hard for English speakers is because we say they’re hard.

Vocabulary

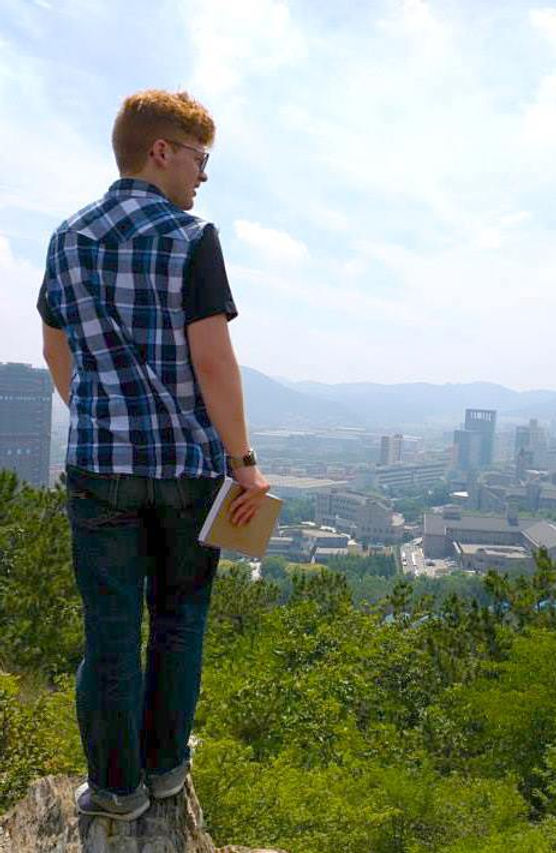

It’s easy to communicate with a vocabulary of 100 words, and you can easily reach that mark in a month. So why isn’t the world full of polyglots? Answer: Most people quit before they get to this critical point. I was talking to locals in China within 8 months of learning, because I was trying hard and staying consistent.

The key is to work on vocabulary and work on it every day. If you can keep this up every day for a month, you’ll be having conversations in no time.

Chinese vocabulary is very simplistic. Most Chinese words, I’ve found, are two syllables long. These zygotic words are usually made of two simpler core words. If you know the simple core words well, you can pretty much guess the meaning.

Let’s take, for example, the word 保, which means “protect,” and the word 存 cún, which means “save.” When you put them together, you get 保存 bǎocún. Can you guess what it means? The answer is “keep.”

Once you know the root words, you can start interpreting new vocabulary before you even look up what it means. And sometimes, if you don’t know a word, you can put together two simple words that mean roughly what you want to say, and sometimes you’ll hit on the actual word you want, even if you never learned it.

Essentially, once you know the primary colors of the language, you can start putting them together to make a whole palette easily.

OK, you say, but what about written Chinese?! Well, I’m about to cover why its bark is worse than its bite. (And again, I have a BUNCH of resources at the end of this page that I’ve gathered over six years, so don’t leave this page until you look at my links.)

Writing System

Next to tones, you’ll hear people complain about the writing system the most.

Once you learn how to read Chinese, you can read and partially understand all the languages that use this writing system, like Cantonese or Shanghainese. You’re also halfway to understanding Japanese Kanji.

When you look at a Chinese newspaper, it seems like a lot to digest, and it is. Even four years in, I sill need my Chinese dictionary open most of the time in order to read books and newspapers. But again—you’ve already mastered a language with a difficult writing system! My point is that it’s difficult, but it’s possible.

In English, we don’t read spelling, we read words. You basically have to memorize how each word is spelled in English, individually. Chinese is no different. Students spend hours and hours of their high school years copying out Chinese characters endlessly. It’s no walk in the park and you shouldn’t expect it to be. But once you break it down, it goes from impossible to doable.

Every character is made of a few basic strokes. First, learn these basic strokes. Then use those strokes to learn the radicals. Once you learn how to read and write radicals, you can start putting them together to build characters. Even the most complicated word in Chinese is made of a handful of radicals. Once you learn these radicals, reading and writing is easier by leagues.

As a mental escape hatch, you can tell yourself that it’s not necessary to learn to read and write Chinese. There are many older Chinese and Taiwanese people who can’t read or write Chinese.

However, if you really want to get into the culture, it’s a must. Sorry, there’s no way for me to sugar-coat this part of the post. Reading and writing Chinese will be the hardest part, but you can do it. It’s possible!

Have a Goal

I learned Chinese from the Confucius Institute, which is a Mainland institution. I followed the course syllabus, learning ten characters a week and some simple conversational elements. If I kept up at this rate, I would sit at a preliminary level by the end of two semesters.

But that’s no goal. For goals to work for you, they need to be specific and doable. “I want to speak Chinese” sounds good, but how will you know when you’ve hit your target? How will you mark your progress?

Proficiency tests are not a great measure of how well you speak, but they do provide a yardstick for your progress. The Confucius Institute provided us students with a proficiency test called the HSK test. The first level tested on a vocabulary of 150 words, which were provided in a list at the end of the syllabus. Over the next few months, I slowly memorized and learned how to use the vocabulary, marking the words off with a pen as I went. This gave me a visual marker for how I was progressing. This way, while everyone prepared for the level one test, I set my sights on level two, and because I had a measurable goal and a way to get there, I aced the level two test.

My main point for this section is this: You’ve got to have a goal! If you say you’re going to be able to speak Chinese in a year, it’s going to be hard to judge where you are in your progress. But having a vocabulary list, a deadline, and a reason, (e.g. I want to learn 150 vocabulary words so I can pass this test 5 months from now) gave me focus and purpose. In just a few months, I was having conversations with locals.

However, this wouldn’t have been possible without my Taiwanese language partner.

Finding a Language Partner

The international student department of my university set me up with a language partner. When we met at a Starbucks and I asked her what part of China she was from, she said she was from Taiwan. To be honest, I was pretty disappointed because I knew nothing about Taiwan. But the more we talked, the better we got along, and I softened to the whole idea of Taiwan.

I had initially learned Standard Chinese, but Taiwanese Mandarin sounded and looked totally different.

As our lessons progressed, I slowly retrained my brain.

- I wiped the er-hua out of my pronunciation.

- Some of my vocabulary got changed, from Mainland lingo to Island dialect.

- When writing, I switched from Simplified to Traditional Chinese.

- Instead of using pinyin to write sounds, I learned to write bopomofo.

You’d think switching from Standard Mandarin to Taiwanese Mandarin would cripple me, but in fact, it just made my skills sharper. Having an extra angle gave dimension to my learning, and gave me a cultural focal point for my studies. It was no longer A Language In a Vacuum.

Maybe that’s the real reason people say Chinese is so hard to learn. The most widely-spoken language in the world, Mandarin is often learned devoid of any kind of specific cultural background.

China is huge. Are you learning Beijing Mandarin? Shanghainese Mandarin? Are you learning Singapore Mandarin or Taiwanese Mandarin? Picking a locale will help you by leaps and bounds.

Review

In conclusion, Chinese isn’t as hard as everyone says it is. Once you break it down into its steps and come at it face-on, you’ll find it a very simple and straightforward language.

It’s easy for several reasons:

- Grammar is practically nonexistent.

- You only need to learn four tones, but keep in mind you’ve already mastered language tonality.

- Vocabulary is simple, and when you come across new words you’ve got a good chance of guessing their meaning.

- The writing system is difficult, but so is the English writing system.

- There are some great resources for learning, and once you’ve got a plan you can tackle Chinese in a few months!

- Finding a language partner will throw you forward by lightyears, and make you much better at conversation than Duolingo. (Not to slander the green owl.)

So what are you waiting for? Let’s get started learning the easiest language! Keep scrolling to find my six years’ worth of resources.

RESOURCES

You’ll spend hours gathering these resources on your own, so bookmark this page and come back as often as you need. Also, if you’ve got any questions or insights, leave me a note in the comments!

Dictionary & Stroke Order

How could I forget MDBG? This very simple website got me through my early Chinese years and continues to be a good resource for me. Very straightforward online dictionary. https://www.mdbg.net/chinese/dictionary There is the option to get Simplified or Traditional characters from your queries.

For your phone, Pleco is an excellent Chinese dictionary. Download it once, use it for your whole life. I have used on the DAILY for the past six years. It’s simple, easy to navigate, and best of all, free: https://www.pleco.com

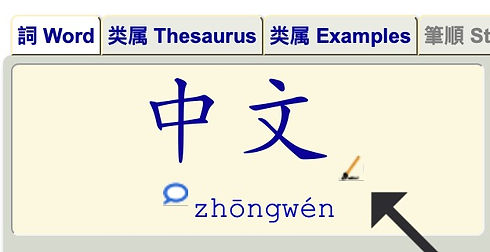

When I was learning to write, I used Yellow Bridge. It’s an excellent resource for starting out. Among the various features of the site, there is a stroke order function that’s infinitely helpful when you’re learning to write.

When you search for a word or character, a pencil icon on the dictionary entry (I indicated it with an arrow) will show you the proper stroke order for writing. The tab called “Strokes 筆順” will show you a larger animation of stroke order, but only for single characters.

Yellow Bridge: https://www.yellowbridge.com/chinese/dictionary.php

If you want to know about the 214 radicals that make up words, you can follow the links below. I’ve included links for both simplified and traditional.

Radicals (simplified): https://www.archchinese.com/arch_chinese_radicals.html

Radicals (traditional): https://www.archchinese.com/traditional_chinese_radicals.html

Pinyin vs. Bopomofo

Unlike English, you can’t rely on sounding out Chinese characters to pronounce them. That’s why Chinese also has various phonetic writing systems, the primary two being pinyin and bopomofo.

I haven’t yet written an article on the pros & cons of Pinyin vs. Bopomofo, and when I do I’ll update this subheader into a link. For now, though, here’s a quick look at the two writing systems.

A brief into to pinyin: https://www.learn-chinese.com/pinyin-lesson-1-introduction-to-pinyin/

A map of bopomofo characters: https://www.omniglot.com/writing/zhuyin.htm

Preparing for the HSK

If you like the idea of using the Standard Chinese Test as an outline for your studies, here are resources on the HSK. Remember that the HSK is used by Mainland China, so it’s simplified Chinese, and uses Pinyin.

For vocabulary flash cards and a memory game, check this out: https://www.yellowbridge.com/chinese/hsk.php

HSK First level syllabus (in Chinese): http://www.chinesetest.cn/userfiles/file/dagang/HSK1.pdf

For more HSK level syllabi:

Leave a comment